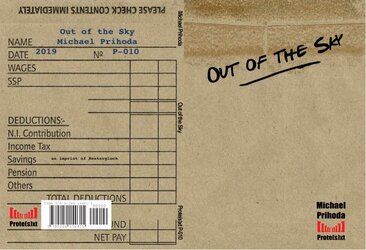

Review of Broken Frequencies by James Alan Riley reviewed by Chris Prewitt96 pages March 28, 2019 Shadelandhouse Modern Press Stay with me here for a moment. What is the distinction between a “cultural shift” and a “cultural crisis”? Having lived in mostly rural and conservative places, I’ve understood the difference largely to be a matter of categorization. Those who can abide by “new” ways of thinking and being, who are not flummoxed or nonplussed by amendments to cultural categories, are likelier to view changes in the culture as “shifts”; whereas a “crisis” occurs when members of a society look upon people, ideas, or conditions that do not easily adhere to previously established acceptable categories with fear, confusion, or animosity. Taken a step further, what does it mean to “categorize,” particularly when that activity has everything to do with how we live—in terms of law, identity, healthcare, etc.—because it has everything to do with our understanding? These are important questions to me for what I hope are obvious reasons. And it is when James Alan Riley touches upon these themes that I am most engaged with his recent poetry collection Broken Frequencies. Time is one of the most important means of constructing understanding. Consider this. One of our greatest beliefs is that people are capable of change. That means people are dynamic, not static. But how could we understand something being dynamic if not for the concept of time? Would a Permanent Now necessitate something (or a subject) being entirely static? Is time not a requisite for dynamism? Likely, we don’t actively think about time in that manner, though. But how many of us wonder what could have been if, say, we hadn’t been sick and missed that day of school, or if we had taken that job instead of the other, etc? The possibilities haunt us. Yet we understand that we must progress in a certain confining manner: that of time. And once we have affirmed our decisions and made our moves, we are committed. We move forward. Possibilities and hauntings come together nicely in the poem “Ghost Story.” I enjoy the following lines immensely: I tell this story as true from the comfort of two lifetimes away… one of the many possible untold versions. These are simple but compelling lines. They brought to mind, as many moments in Broken Frequencies did, this line from James Wright’s poem “Today I Was Happy, So I Made This Poem”: “Each moment of time is a mountain.” And it’s true: consider all the things that had to transpire in just the exact manner that they did in order for you to arrive at this moment in time. Each of us are climbing over Everests each moment of our lives. And it is not unusual to look back at previous expeditions and contemplate these journeys: how long ago a particular journey was, what other journeys may have been but never were. Crucial to categorization is language. Generally speaking, poems that dwell on language, particularly panegyrics to syllables, don’t do it for me. In saying that, when a poet draws attention to language in a way that is not merely in veneration, I take notice. Consider the opening poem “In a World Without Birds”: They know a bird when they see one. They recognize feathers and wings, but that’s about as far as they can go beyond the different colors… the generic woodpecker or chicken. In a world without birds, all ducks are the same duck quacking in circles on some stagnant, unkept pond. Clearly there is a relationship between understanding and language. We distinguish male cardinals from bluejays not only by our ability to distinguish the physical attributes of these birds but also in our ability to name (to categorize). When this ability is stymied, so is our understanding, at least until someone can correct us, can give us the language that we need. This is not inconsequential. It is how we understand our lives. But even the most verbose and engaged and eager to learn amongst us get it wrong, for “Distance, like memory, can be deceiving,” as the speaker tells us in “Theories of Elegance.” Further, there are unavoidable failures: I am trying to play a song I cannot play, trying to explain something that cannot be explained (“Playing My Brother’s Guitar”). And then there’s disease which incapacitates. What appears to be Alzheimer’s disease alters reality for a man named Walter in my favorite poem of this collection, the tragic “The Catherine Wheel.” Elaborating on the events that occur in this poem would only spoil the poem, so to say the least this poem evidences the loss of language and categorization, of distinguishing between past and present, and how these losses make existence difficult. (I would ask that as you read this poem to pay attention to Walter’s character. He was once a man preoccupied with his future and how certain critical junctures in his life posed risks to the comfortable future he wanted.) Broken Frequencies deals in heavy themes, no doubt, but it is far from inaccessible. The language is clear, and a poem never strays from the heart. I hope you take the time to journey with Riley in his collection of poems. I think you will be happy that you did. Reviewer's Biography Chris Prewitt is the author of Paradise Hammer (SurVision Books), winner of the 2018 James Tate Poetry Prize. Chris's poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Twitter correspondence welcome: @poetcprewitt. Review of Out of the Sky by Michael Prihoda reviewed by Emma Holdaway, KD's Book Review Editor In her experimental style, Book Review Editor Emma Holdaway takes a journey through Out of the Sky by Michael Prihoda. Check out her review HERE! Find out more about Prihoda's work here: https://michaelprihoda.wordpress.com/ Planet in Peril, by Isabelle Kenyon (editor), reviewed by Pat Edwards Hardback 128 pages 2019 Copies of this anthology may be purchased here: https://www.flyonthewallpoetry.co.uk/product-page/pre-order-planet-in-peril In the mid 1970s when I was doing my A levels in Botany and Zoology, it was all CND and pollution. Since then I seem to have heard more and more about global warming, plastic, fires in the Amazon, habitats and species becoming extinct, on and on. And what have we really done to counter this? Very little. Instead, we seem to have been sleep-walking and being pretty ineffectual. When I hear Greta Thunberg, I want to both cheer and weep; joyous that a young woman is so lucid and powerful in speaking truth to power, cynical that her appeal can cause the massive shifts in business and politics that are needed to make a real difference before it’s too late. Planet in Peril is a voice for us ordinary, powerless folk who don’t really know what else to do but document what we stand to lose and record words and pictures of protest and comfort. I like that the book has sections devoted to the Earth’s ecosystems, our oceans, and the impact of us humans. I like too that it examines the future, particularly through the eyes of the young. Featured poet, Helen Mort, opens with a provocative piece where she imagines coming back as a tree, “when the sky glows orange, I’ll be steadfast.” The poem recognises the huge role trees play and thus far their ability to “persist,” be “blunt phoenix”. Between the poems and photographs is an easy to read commentary giving clear, verified information and statistics about the natural world and the delicate balance of ecosystems and organisms. Poems chart the silencing of trees, animals giving birth, the fragrance of blossom, ice, microscopic marine plants, snow on a child’s face, hot summers, corals, and our attempts to say sorry. Many of the photographs make the reader stare into the eyes of animals on the brink. This is an unnerving interaction, forcing us to see these creatures as just like us, fighting for their families, their territory, for survival. Animals, birds, insects, small and large feature as essential links in the chain. The photos show fauna in their prime, brightly coloured, both muscular and frail, in flight, fearful, majestic and wild. Turning again to the poetry, Rachel Ikins’ piece uses familiar personification to characterise the planet as “a big, soft woman” ravaged by extremes of weather until “exhaustion takes her.” This simple device is powerfully handled and is a useful means of helping evoke a human response, giving us a visceral connection to “an anonymous woman forgotten by the entitled masses who wrangle and tromp all her secret places.” Phil Coleman’s “Red List” is a damning poem set out as an alphabetical catalogue of man-made disasters and inventions, “Landfill. Light pollution. Logging…Urban sprawl. Unchecked. Urgent.” Rachel Haddy’s poem “Battlefield” draws comparisons between what mankind has done and warfare. Her emotive vocabulary evokes ancient fights “on the beaches”, assassinations and “the war dead.” Amongst the poems we even find a haibun and a villanelle. Joanna Lilley’s bleak poem “Specimen” starts with the horrific possibility that “there will come a time when there were only two humans left in the world and they will be dead. You, perhaps, and me.” These displayed human remains will represent the “alleged architect of annihilation.” Elaine Beckett takes us further into the future in her “2084,” “the apple pip is still in its plastic bag as transparent as the year they sealed it.” How shocking that the commonplace may become a precious relic. Featured photographer, Emily Gellard, captures the cold, blue magnificence of an Antarctic glacier, massive and riven with alarming fissures. By contrast, her Macaw photo is a brilliant close up of the dazzling red feathers around the bird’s eye. Fitting then that in “Yellow Beak” by Christopher Hopkins we encounter “the carcass of a seabird” and learn how it met its demise: “And there gather the choir that sang its death; shaped pellet trails and bottle tops, the weathered beads of nameless colour, the fish and shrimp of its plastic suppers…a stomach full of death.” In the end, the young writers turn unashamedly to rhyme where they can find no reason. Take Chanpreet Samra’s “We’re Sorry, Mother Nature,” and Ethan Anthony’s “The Tale of Two Lime Trees.” The young people pose questions, mourn loss and the waste of resources, make accusations, as at just eight years old Lilian Amjadi Klass remarks, “the rubber, the metal, the wood and the lead, disaster at your fingers.” Elizabeth Train-Brown found the only way to preserve the Tigress in her poem was to have “her tattooed on my back – an elegy, a ballad, something that I could soak into my flesh like smoke.” When a young person like Edan Osborne aged twelve tells you “I’m cracking under pressure and shaking to the core; stop this global warming – I can’t take any more”, we have to return to where we started and grasp Helen Mort’s glimmer of hope: “If I must come back, let me come as a small tree, slow-growing, sturdy, hesitating on the ladder the sun throws down to me.” Planet in Peril is a haunting book, compelling for its honesty and truth. It deserves to be a resource for both education and protest, a record of our time. I wish it well on its journey out into the wild. It’s dangerous out there and some people still don’t care or want to listen. I think what is has to show and tell is brave, gentle, angry and worthwhile; poetry and photography as art and armour. Reviewer's Biography Pat Edwards is a writer, workshop leader, reviewer and general poetry activist from Mid Wales. Her debut pamphlet, Only Blood, was published by Yaffle Press in October, and her next will be out with Indigo Dreams in 2020. Pat hosts Verbatim poetry open mic nights and curates Welshpool Poetry Festival. |

Book ReviewsWelcome to KD's re-vamped blog, where you'll find book reviews by our editor Matthew Weddig. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

- Home

- About

- Press

-

Issues

- Issue 51

- Issue 50

- Issue 49

- Issue 48

- Issue 47

- Issue 46

- Issue 45

- Issue 44

- Issue 43

- Issue 42

- Issue 41

- Issue 40

- Issue 39

- Issue 38

- Issue 37

- Issue 36

- Issue 35

- Issue 34

- Issue 33

- Issue 32

- Issue 31

- Issue 30

- Issue 29

- Issue 28

- Issue 27

- Issue 26

- Issue 25

- Issue 24

- Issue 23

- Issue 22

- Issue 21

- Issue 20

- Issue 19

- Issue 18

- Serenity

- Issue 17

- The Audio Room

- Issue 16

- Issue 15

- Issue 14

- Play It Again

- Issue 13

- Issue 12

- Issue 11

- Issue 10

- Issue 9

- Issue 8

- Issue 7

- Issue 6

- Hand to Mouth

- Issue 5

- Issue 4

- Issue 3

- Issue 2

- Issue 1

- Submissions

RSS Feed

RSS Feed